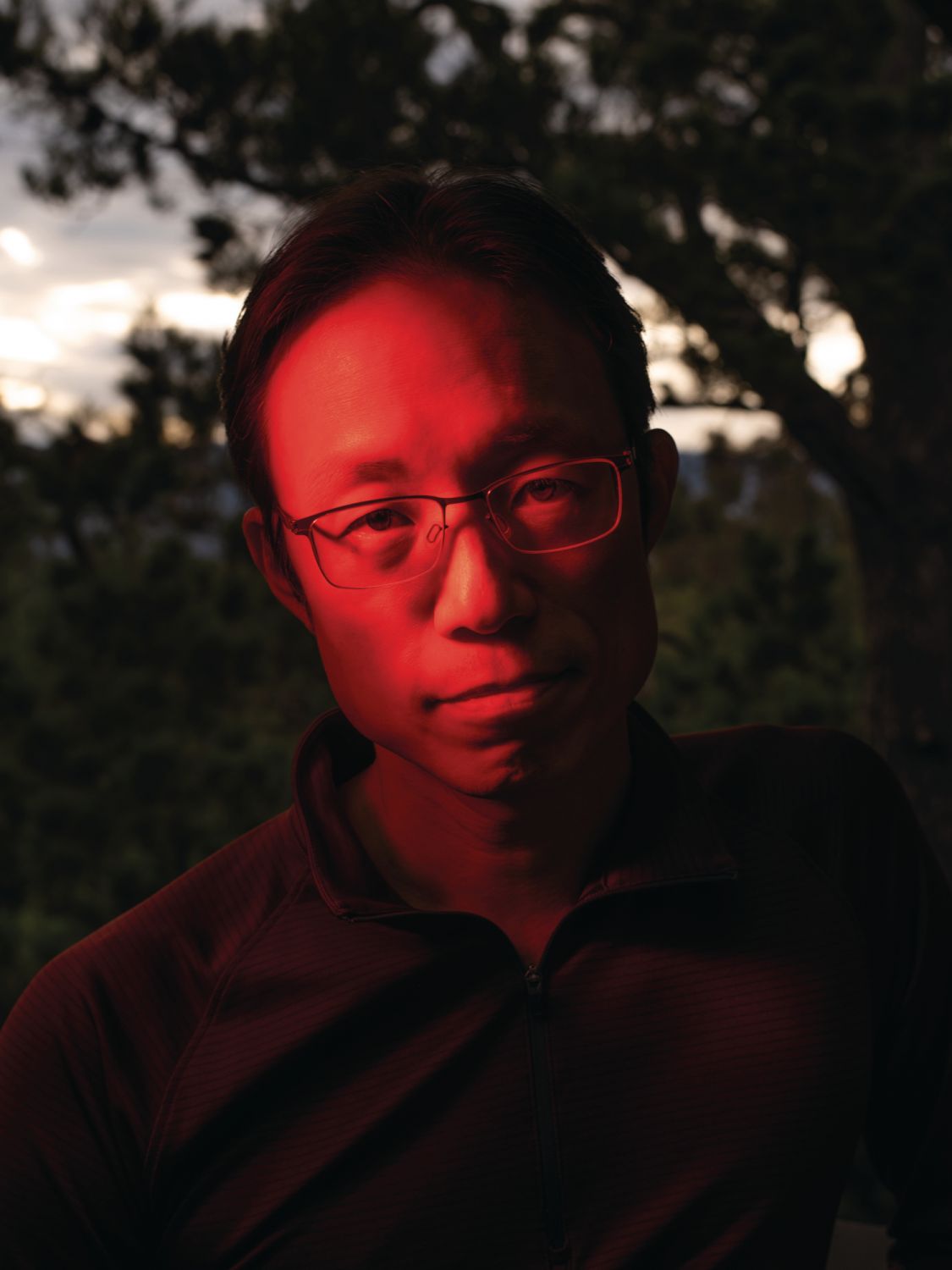

For Yat Siu, the man behind the launch of The Sandbox, our future is virtual and the metaverse can’t come soon enough

You’ll have heard a lot about the metaverse recently. Yat Siu is busy building it.

“The most important thing to understand about the metaverse is, for most of us, our virtual existence is already more important than our physical one,” says Siu. “If you’re detached from the online world, you’re a lesser human today: you can’t connect with people or promote yourself.”

Animoca Brands, the game producer and venture capital company of which he is executive chairman and managing director, has pivoted dramatically in recent years towards blockchain, NFTs and the metaverse, meaning a network of fully functioning 3D virtual worlds, accessed using VR, in which users can live a second life. The company is doing so armed with a valuation in the billions and a war chest that has allowed it to invest in more than 150 related companies—including one, open-world game The Sandbox, which has blown up spectacularly of late, and which is currently looking like a good bet for the first fully functioning metaverse environment.

Read more: A Metaverse Afterlife: Zhang Huan Talks NFTs and Spirituality

“We’re living in a kind of pre-metaverse. Then the question is: how do I ensure, in this digital nation, that I have rights? The problem is you don’t actually own anything; Facebook can take it away from you at any time,” Siu says. “But through this concept of Web 3.0, we can now own part of the internet. Creativity can be rewarded with equity. That’s our north star, our mission."

Metaverses might be the subject of much hype right now, but they’re not entirely new, largely because of gaming. In a so-called sandbox game like Minecraft, for example, players are involved in building the world. But the metaverses currently under development will use VR to create an entirely more immersive experience, in which users become part of a virtual world, navigating it from a first-person perspective much as they would the physical world. NFTs, aka non-fungible tokens, meanwhile, could provide the keys to unlock it. They represent proof of unique digital ownership, stored on the blockchain, the technology best known for powering cryptocurrencies; while assets can be copied, ownership can’t be forged and can be traded.