Valentino’s Pierpaolo Piccioli has long been beloved for pushing fashion forward with his magical yet meaningful couture. This season, he transcends the craft with the help of 16 contemporary artists

Don’t call Pierpaolo Piccioli an artist. He insists.

“It’s provocative to say this, I know, but fashion is not art to me,” the designer says in a hushed, thoughtful tone, his Rs curling through a thick Italian accent. “Fashion needs to work with the body, there is a practical purpose, but art is free from constraint.”

Piccioli is perched across from me on an ornate sofa, wearing his black hoodie-and-slacks uniform, square Ray-Bans firmly planted on his nose as he swings a sneakered foot over his knee. He continues, “Both are languages with which you can express yourself and your values. Fashion is my language.” On a simmering July afternoon, we are at a preview in Paris, beneath the chandeliered ceiling of a grand salon in Place Vendôme, several gowns dotted around us, each almost camouflaged against a corresponding artwork. I imagine it is what the inside of Piccioli’s head might look like.

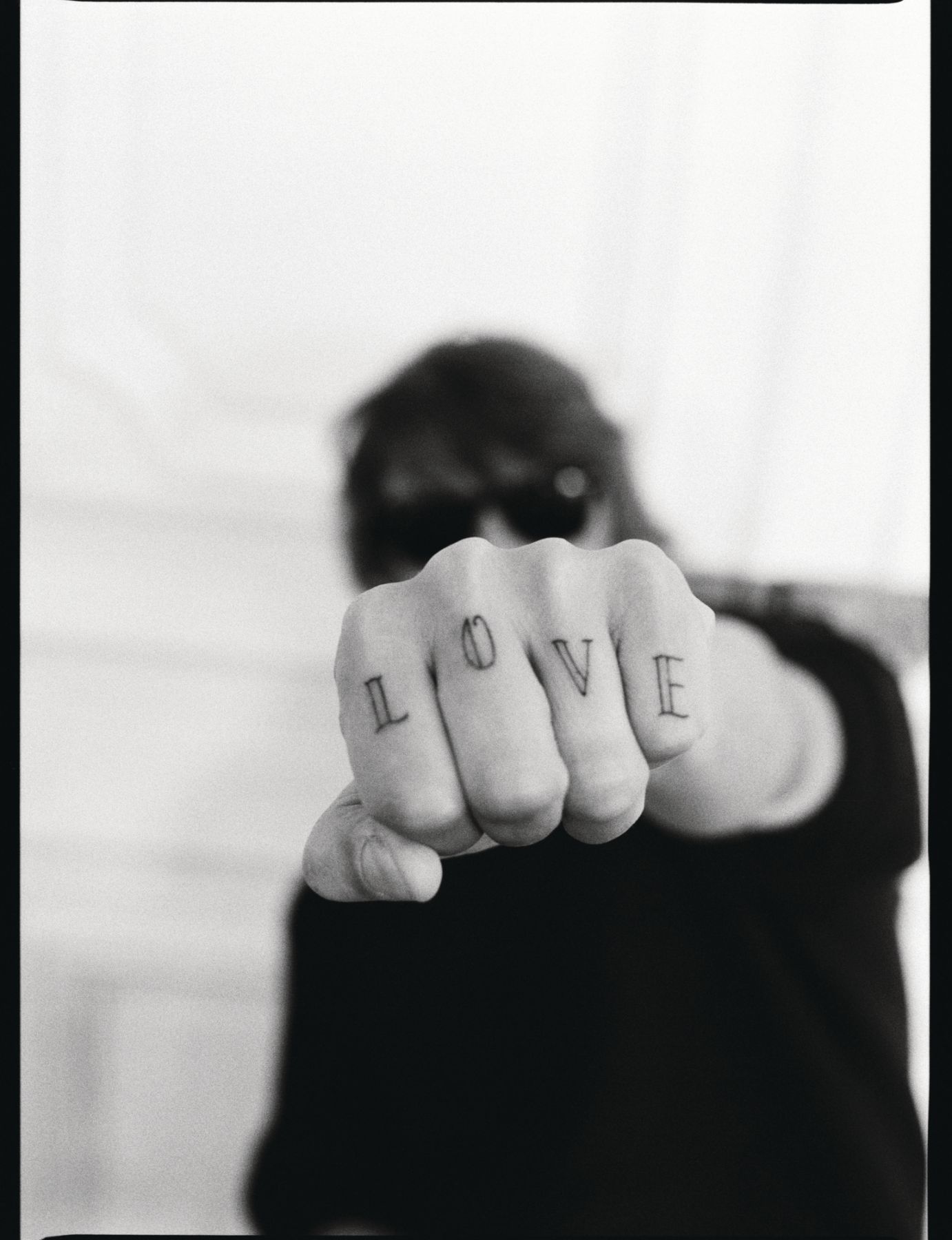

The pieces, from cashmere capes to majestic ballgowns, are part of his latest couture collection, Valentino Des Ateliers, for which he enlisted 16 contemporary artists from around the world with the help of curator Gianluigi Ricuperati to partake in an “exchange of ideas”; he sees the work as more than just a collaboration. “I didn’t want to do an ‘artsy’ collection; I wanted to do a collection that’s inspired by a conversation between humans, that’s about empathy, about connection—especially during a time last year where there was no connection—and about love,” he says.

If this all sounds a touch saccharine, know that Piccioli, who has made Valentino synonymous with unabashed romanticism, is sincere. Since becoming creative director (for eight years from 2008 alongside Maria Grazia Chiuri, now artistic director of womenswear at Christian Dior, and solo since 2016), Piccioli’s ready-to-wear has had fans lusting over his indulgent designs—the Rockstud, a design he popularised on Valentino accessories, or the menswear collection he produced with Undercover’s Jun Takahashi featuring pieces printed with lines of poetry come to mind. But couture is where Piccioli’s vision thrives unfettered. “To me, couture is a philosophy and approach about people, it’s not just about technique.” This is something reflected in every element of his work, even down to the appellation: as per a tradition Piccioli started, each couture look is named after the seamstress who made it.

See also: Met Gala 2021: The Best Jewellery Pieces We’re Lusting After

As such, Piccioli wasn’t interested in simply printing works of art on garments but instead sought to bring art to life through fashion. “In order to do this, I had to catch the spirit of the artist, not only their colours or the shapes of their brushstrokes,” he says. He points behind the sofa to a blood-red ballgown featuring what resembles a collage of arms embracing. The piece was created with artist Alessandro Teoldi, whose original artwork was recycled from old aeroplane blankets. Piccioli therefore chose to recreate the shapes with archival fabrics of the house, including those used by Valentino Garavani himself. “To me, [this work] is a story of how memories are part of our present,” says Piccioli.

Quite often those who are fortunate enough to be witnesses at his spectacles speak of being moved, sometimes even to tears. Perhaps it’s because Piccioli says he himself must first be moved by his own creations. What strums his heartstrings could be a particular shape draped just so, or a colour so succulent you can almost taste it. It is this criterion that Piccioli used to select the artists for the project. “I was just drawn to certain works where I felt something, so they’re all emotional and personal to me; only when I feel something can I deliver emotions to other people,” he says.