These previously undocumented coral species shed light on how the city’s marine environment may be more diverse, and yet more fragile, than we imagined, according to Qiu Jianwen and Sam Yiu King-fung

It started as just another summer’s day of analysing coral health in a Hong Kong Baptist University laboratory. Then, suddenly, Qiu Jianwen and his colleague Sam Yiu King-fung spotted something they had never seen before: the coral being eaten by some of the coral-eating nudibranchs they were studying was bright orange and violet. They had inadvertently discovered what would turn out to be three new species.

Hong Kong isn’t known for colourful corals; these are more commonly found in diving paradises like Tubbataha Reef in the Philippines or Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, where the warmer tropical waters and gentler underwater terrain enable the growth of vast, brightly coloured communities. Here in Hong Kong, where nearly 90 species have been identified, most hard coral is pale, greyish and monochrome, as the relatively colder subtropical water temperature in winter constrains coral growth.

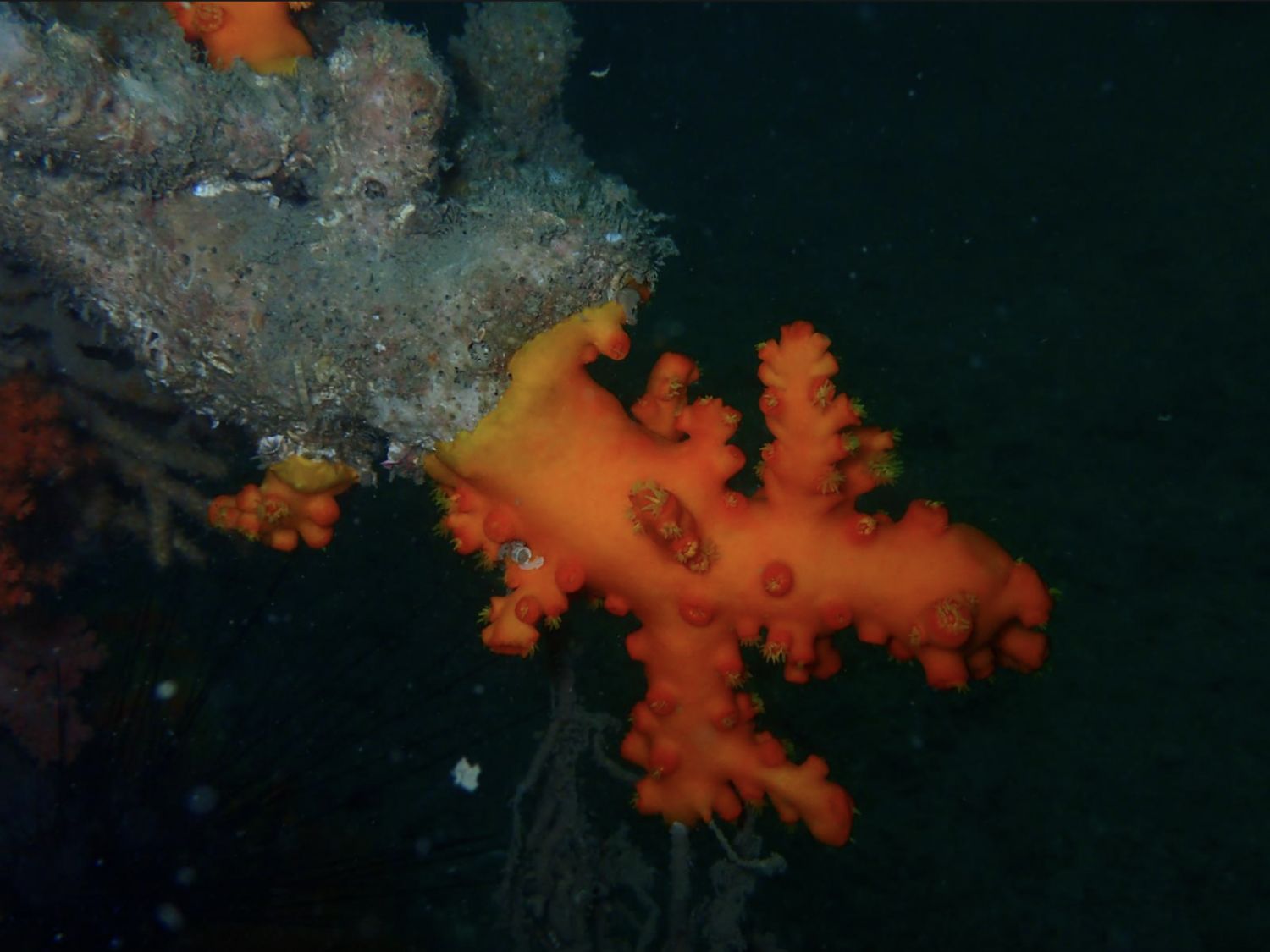

At the sight of this anomaly, Qiu, who is the associate head of the department of biology, and Yiu, a researcher working with Qiu at the time, returned to the site where they collected the nudibranch specimens to conduct an in-depth underwater search. As they dived to ten metres below sea level, radiantly coloured corals—with polyps and branches spreading out like sparks from a firecracker—loomed in the shadows.

After cross-checking local catalogues and public DNA sequence databases, the team confirmed that what they were seeing were three undocumented species belonging to the sun coral or Tubastraea genus. Its common name is derived from the polyps’ golden yellow colour as seen in known sun coral species in the South Pacific. Qiu and Yiu named their species Tubastraea dendroida, Tubastraea violacea and Tubastraea chloromura.