As we celebrate Halloween, Tatler unravels the myths and legends of the spookiest jewellery known to mankind

Jewellery has the power to hold on to memories, emotions and intentions. Which is why they are often heirlooms, to pass history down from one generation to the next. Sometimes, along with the history comes luck—both good or bad.

Here are some real-life jewels with a notorious reputation.

In case you missed it: Why Is the Kohinoor Diamond, Inherited by Queen Consort Camilla, So Controversial?

The Black Prince's Ruby

Dubbed “The great imposter” this 170-carat red jewel was in fact not a ruby at all, but a cabochon spinel said to be mined in Afghanistan. It was reportedly first mentioned in the 14th century by Don Pedro the Cruel of Spain, whose lust for the gem resulted in his murder of Abu Sai'd, the Moorish Prince of Granada who owned the spinel. Don Pedro took off with his precious rock, and thus the curse began.

After that episode, the gem proved to be fatal for all those who possess it: Edward of Woodstock, “The Black Prince” who demanded the gem from Don Pedro as the price for an alliance forged between the two men, suffered poor health and died before his father, King Edward III of England. Had he lived he might have been King Edward IV, but his death made way for his younger brother to reign as King Richard II instead.

The stone was owned by the line of British royalty including King Charles I who was beheaded on account of treason in the year 1649.

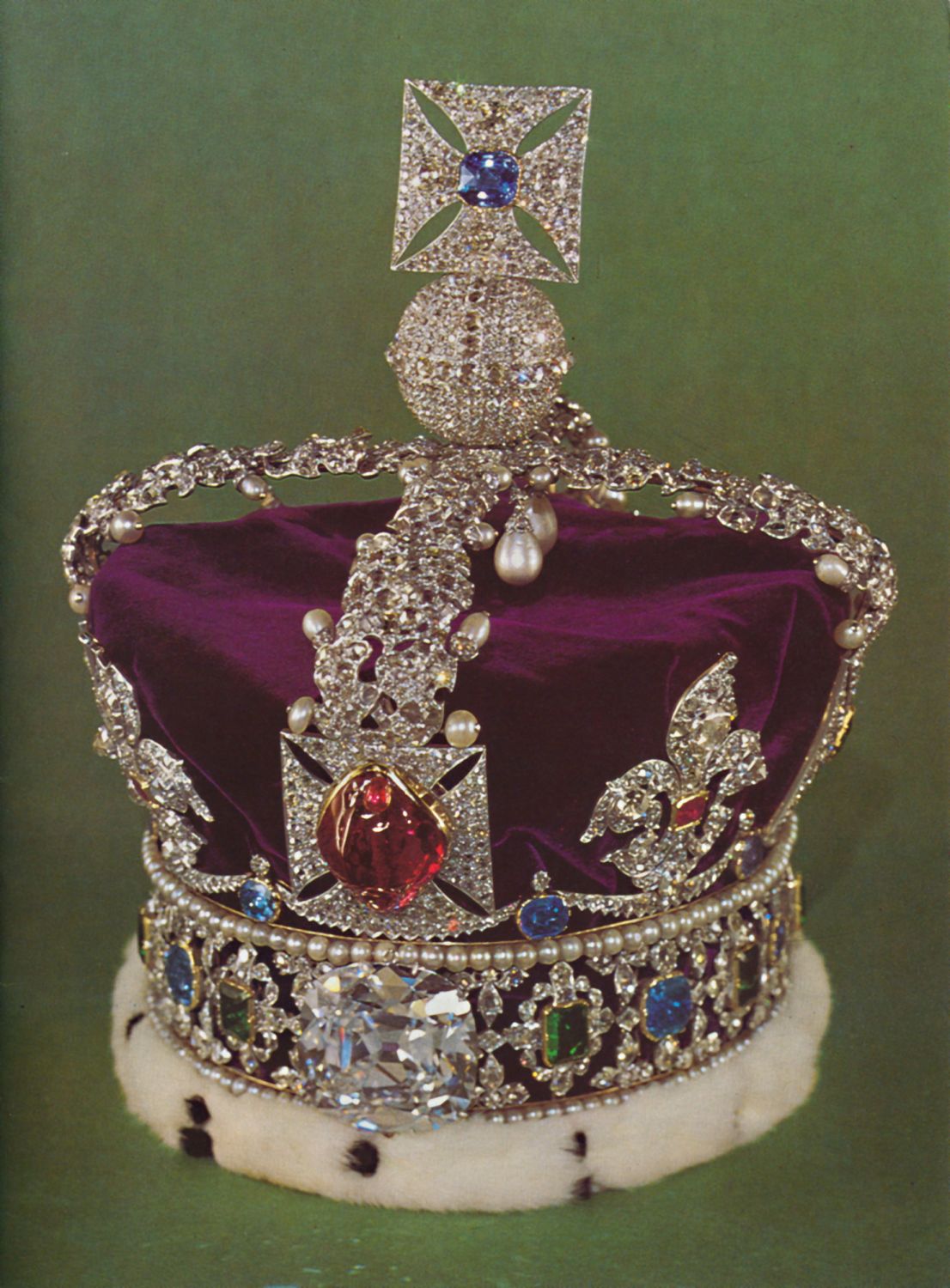

It then passed on to King Henry VIII and his daughter Queen Elizabeth I, who famously reigned over the Elizabethan Golden Age but whose death also marked the end of the Tudor line. However, despite its notorious past, it continues to adorn the imperial state crown of the royal family in UK.