Nearly 50 years after Ramon Valera's death, not many have surpassed his mastery of design and innovation

This feature story was originally titled as A Cut Above The Rest, published in the August 2003 issue of Tatler Philippines.This story was copied as is, changes were made only on the lead paragraph above. Three years after this article was published, Ramon Valera was conferred the title of National Artist for Fashion Design.

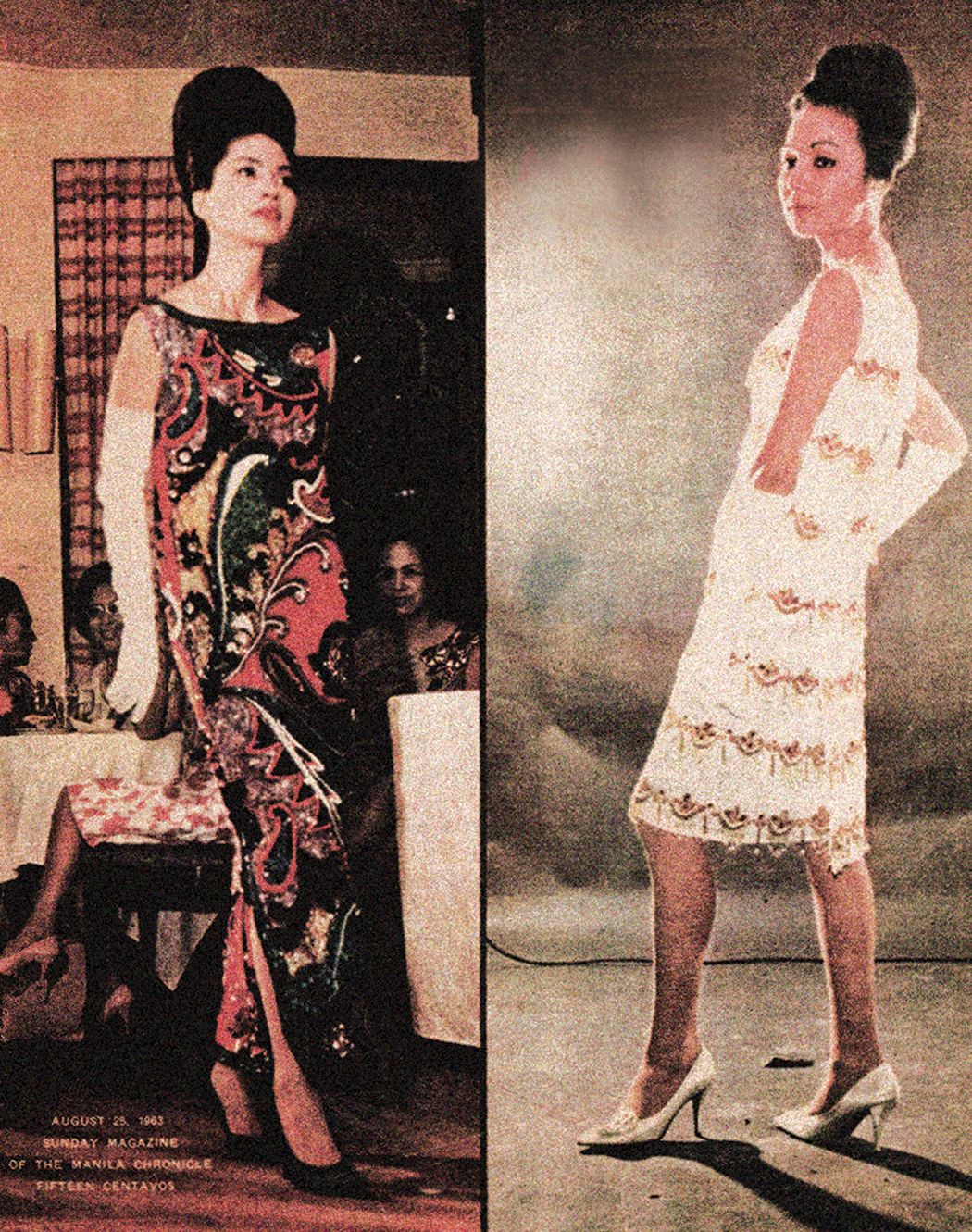

He was celebrated for his ingenuity and craftsmanship, for revolutionizing the national costume, for his masterly embroidery and beadwork and for translating Philippine motifs into contemporary terms. The greatest of all was his manipulation by cut—he would sew a dress to perfection without using a pattern. Ramon Valera was the Dean of Philippine Fashion as he was a creative innovator.

He was born on August 31, 1912, to a well-to-do family. His father, Melecio, was a partner of the tycoon Vicente Madrigal. Since his youth, Valera had been a natural in fashion design. His mother, Pilar Oswald, noticed that the dolls displayed on the piano would suddenly have new clothes. Did he study or was he self-taught as his relatives claimed? In an essay for the terno exhibit at the Cultural Centre of the Philippines, Cris Almario wrote that Valera studied under Mina Roa, who made ternos for the elite before World War II. She taught him European construction and draping techniques. In his teens he made Sunday clothes for his sisters, who would be noticed by the churchgoers. An early attempt was making a yellow and purple dress, a combination unheard of in those days, for his sister to wear on College Day.

Valera studied at La Salle and was one semester short of completing a commerce course at the Far Eastern University. When his father died, the lawyer cheated on the will since Valera's widow didn't understand English. This left the family in an unstable financial condition. Valera quit school and started to work.