With manufacturers and consumers becoming increasingly aware of the fashion industry’s potential to wreak havoc on the environment, we gathered a group of sustainability trailblazers with intimate knowledge of the supply chain for a round-table discussion of some of the most pressing issues facing the industry.

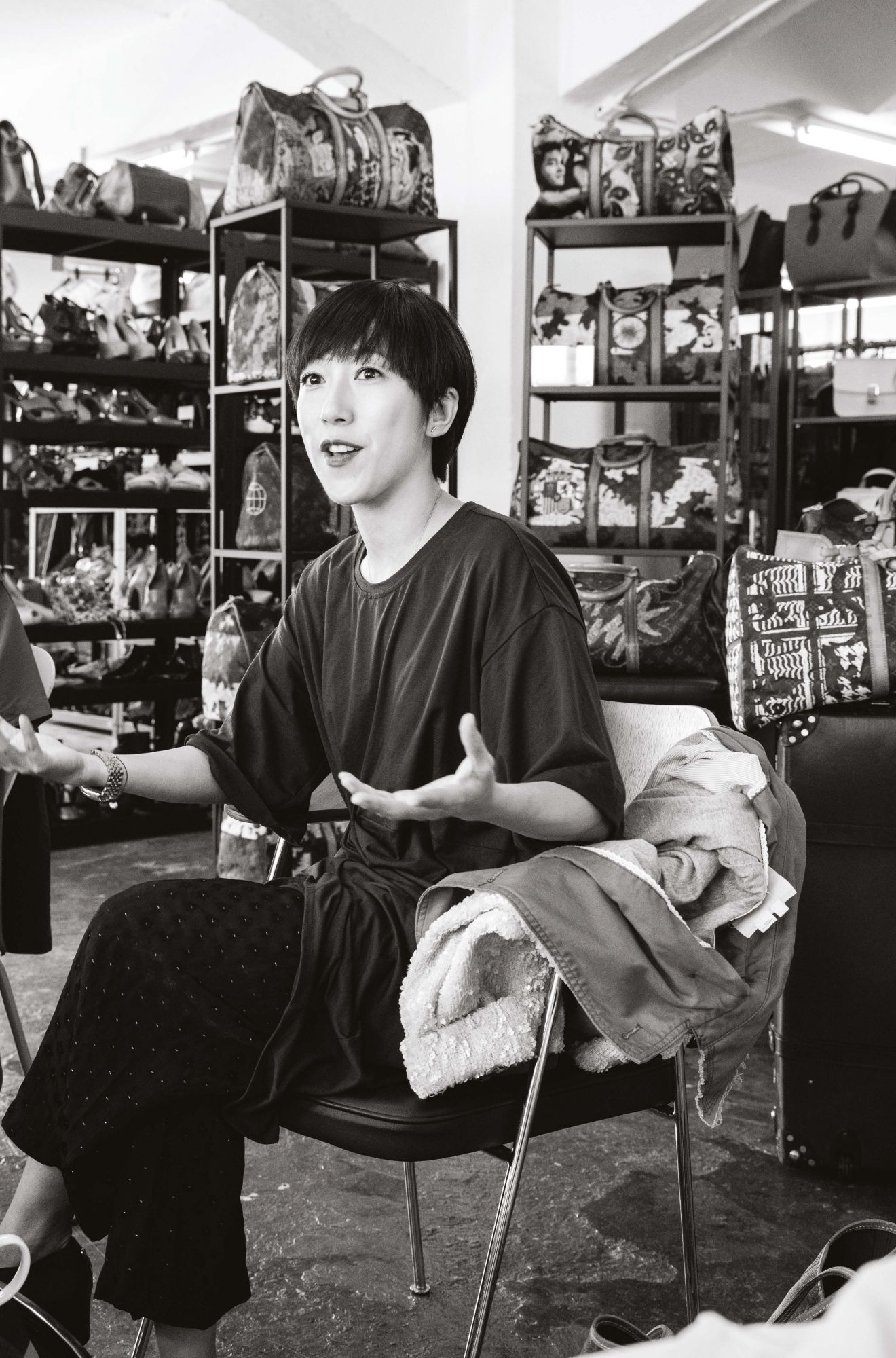

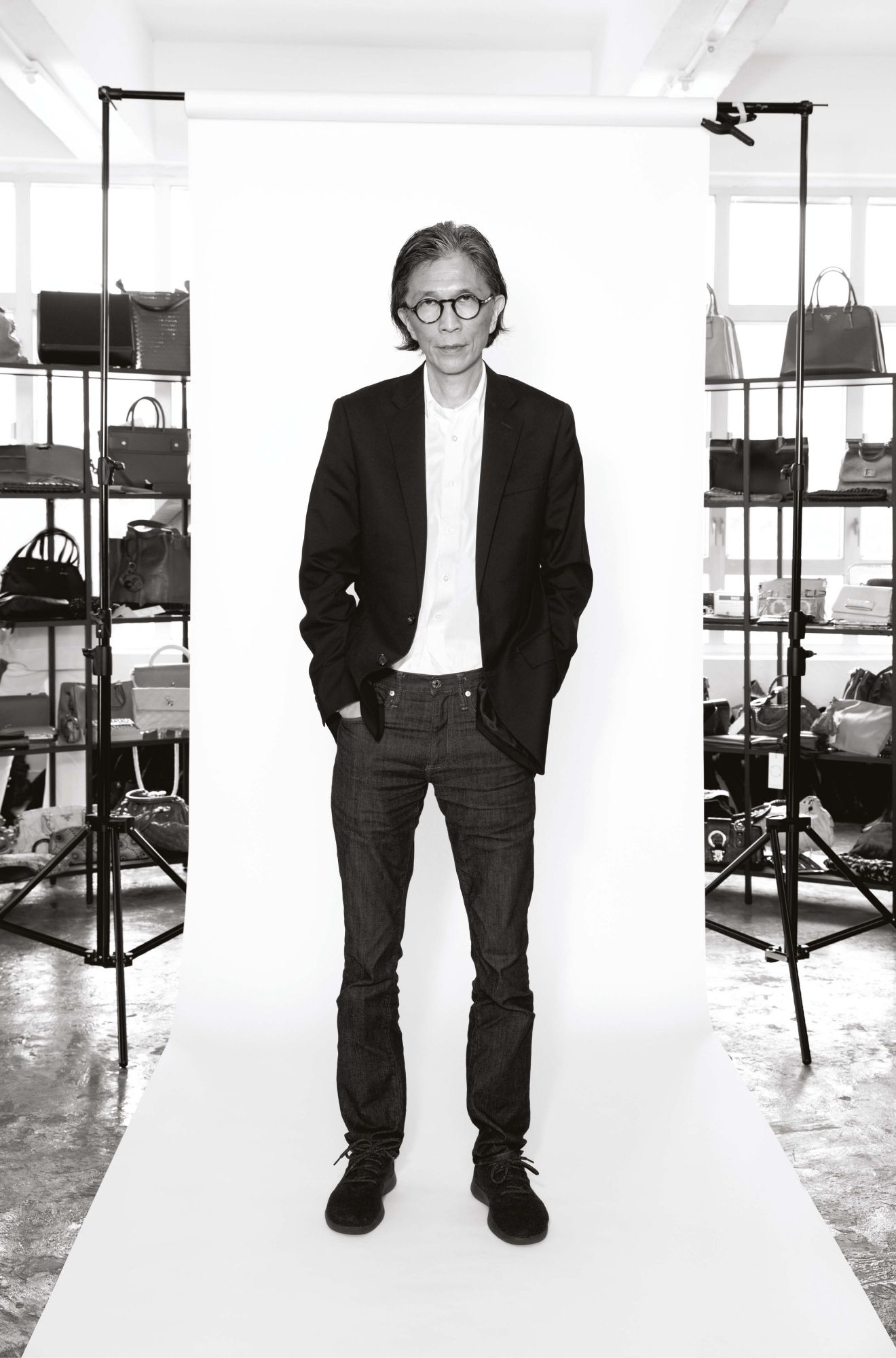

“It makes me want to cry,” says Hula CEO Sarah Fung, one member of the Tatler round-table discussion, as Edwin Keh, CEO of the Hong Kong Research Institute of Textiles and Apparel, brings up one of many unsustainable practices of the fashion industry: the destruction of unsold goods by luxury brands to maintain scarcity and thus high prices.

After oil, fashion is the most polluting industry in the world today, causing environmental degradation and pumping out ever-increasing amounts of greenhouse gases.

Despite efforts by luxury and mass fashion brands to become more eco-friendly—huge conglomerates and speciality retailers including Kering, Burberry, H&M and Inditex, for example, have signed the UN’s Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action, which pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent by 2030—progress is slowing down, according to a report in May by the Global Fashion Agenda, Boston Consulting Group and the Sustainable Apparel Coalition.

Today there’s a growing movement in the fashion industry to adopt sustainable practices by transitioning from the linear production model of “take, make and waste” to a more circular model that preserves value and returns materials to the marketplace.

This is being achieved in both the manufacturing process (think responsible labour laws, upcycled materials and zero-waste manufacturing) and consumption (such as through vintage and second-hand trading). But each part of the chain comes with its own set of challenges.

The Challenges

Even in the 21st century, certain mindsets hold the industry back from making positive progress. During a recent visit to the Paris headquarters of a luxury brand, Edwin questioned senior directors about their continued use of animal leather.

“They said it’s because they’ve been doing it for 100 years,” he says. “It’s almost sacred—the idea that it’d be a compromise if they don’t do it exactly this way. But, actually, they’ve just locked themselves into this world they’ve created and are fearful of deviating from it.”