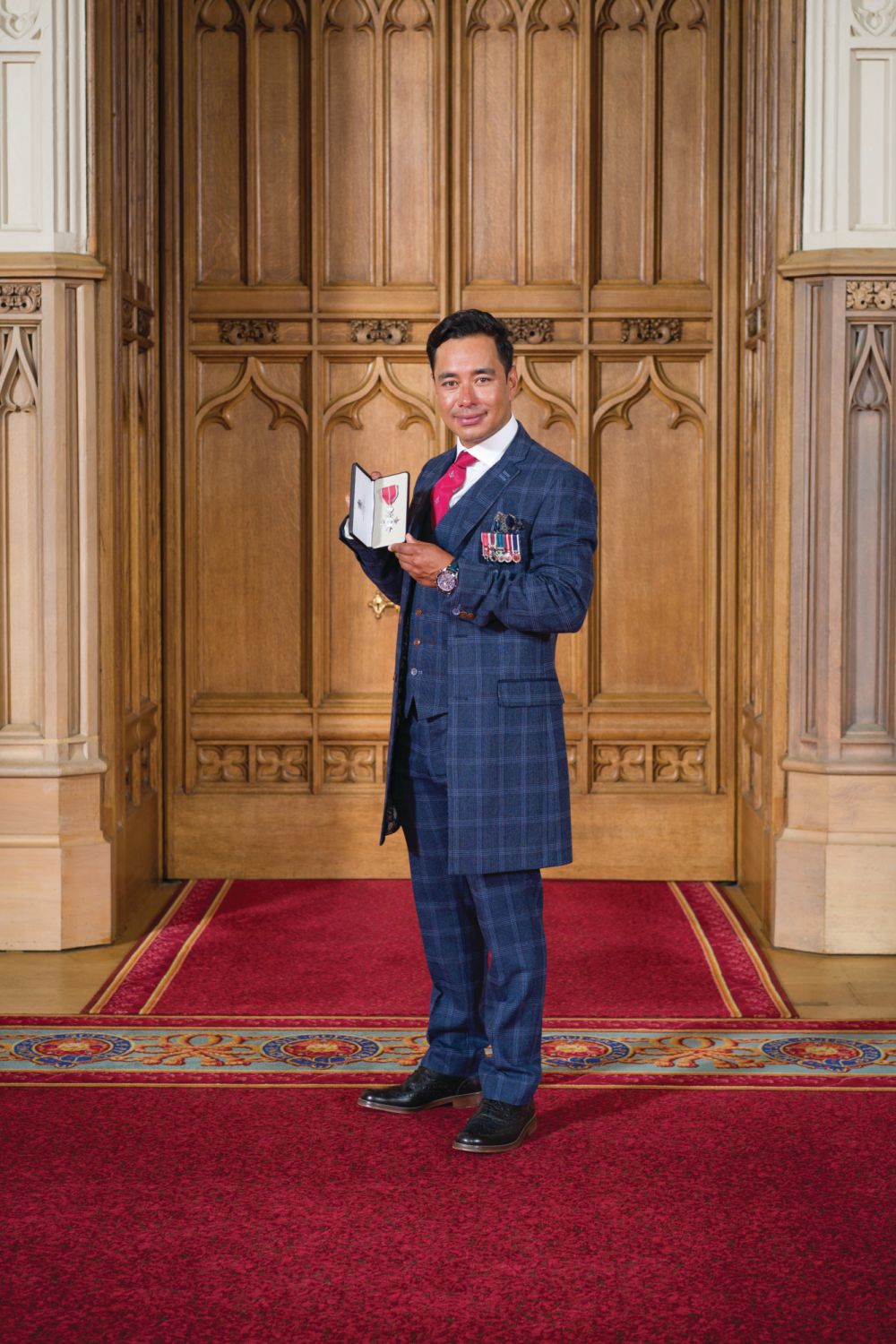

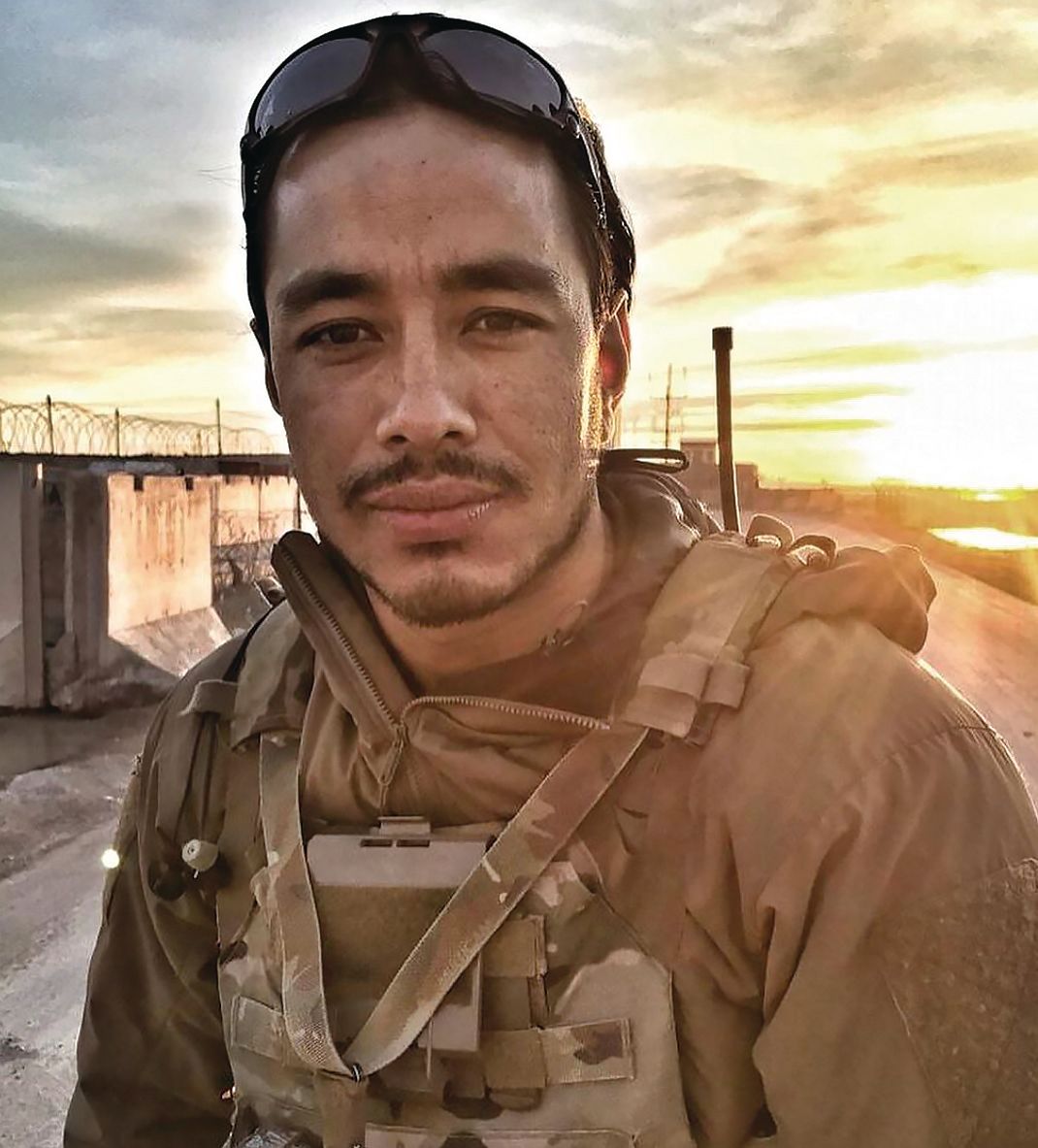

After years spent picking off climbing records, Nirmal “Nims” Purja sets his sights on his toughest conquest yet

When it comes to mountains, Nims Purja has seen and done it all: his record-setting climb of all 14 of the world’s highest was immortalised in a hit documentary; he holds several speed records for multiple ascents back to back, and led the first team to summit K2 in winter—without supplemental oxygen; and he has summited Mount Everest seven times and founded a guiding company. Through planning, dedication and faith in his own abilities, he has built a reputation for achieving anything he sets his mind to. However, this year, when he set out on a new challenge—an extreme litter-picking mission on the world’s tallest mountain—it didn’t quite go as planned.

In case you missed: Could Wilson Cheung Be the First Hongkonger to Conquer the Alps’ Peaks?

“To be honest, I didn’t expect it to be that tough, and I’m a very strong climber; the strongest climber in the world. My team was with me trying to pull the rubbish out of the snow at 8,000m, which was very hard,” he tells Tatler after returning from a two-and-a-half month expedition during which 500kg of rubbish was removed from the highest parts of Everest. The trip marked the expansion of The Big Mountain Cleanup a year after his foundation launched the project on Manaslu, the world’s eighth-highest peak, to address the mounting issue of human-made rubbish in the Himalayas. Purja and a team of Nepali climbers headed to Everest’s “death zone”—the section of the mountain above 8,000m where low oxygen causes the human body to deteriorate—to remove as much rubbish as they could carry. Altitude, coupled with logistics and each climber only being able to carry about 30kg down per trip, made both trips arduous, yet galvanised Purja for further attempts. “We’re gonna have to go again next year; maybe it’ll take another three or four years, but we are determined to do it.”

Now back at sea level, Purja says it’s up to climbers to promote better management of waste in the mountains, and be willing to pay extra to subsidise its removal and fund projects in the region, which relies on tourism. Dedicated expeditions will increase the project’s success, he explains, as when they are guiding clients on an expedition, “There’s a limit to what we can carry because we also have to bring the clients’ kit and all the equipment down. So this has to be a completely separate clean-up project; we’re going to do it next year with a bigger budget and team. The awareness is out there now, though. At least we have achieved something.”