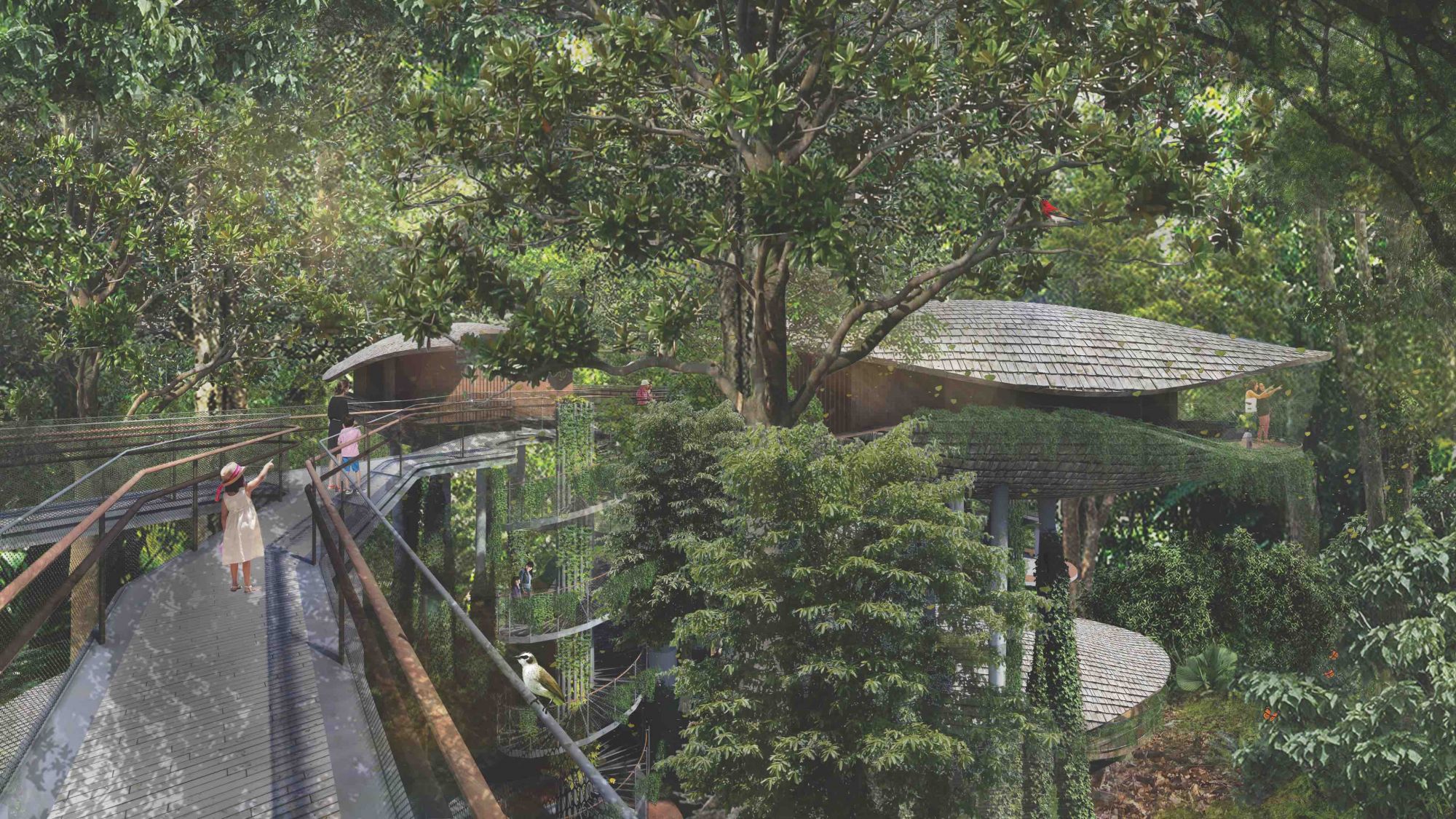

Singapore is already a poster child for biophilic architecture but architects and designers are reinventing new ways of living with the natural world

When Jewel Changi Airport opened last year, the world marvelled at the ingenious idea of incorporating a waterfall and verdant gardens into an airport mall. This feature is not only aesthetically pleasing, it also relieves shopper and traveller fatigue. The project, which was designed by Israeli-Canadian starchitect Moshe Safdie, added to the list of noteworthy biophilic architecture in Singapore across typologies, reiterating the tiny island’s reputation as a nature-infused city-state.