Adding the Run Run Shaw Creative Media Centre to his many contemporary designs, architect of the new City University building, Daniel Libeskind, reveals the emotional connection found in all his projects

The crystalline Run Run Shaw Creative Media Centre, City University’s headquarters of education and training in creative media in Kowloon Tong, is Polish-born architect ’s latest addition to his outstanding collection of works. Knowing that it will be a creativity hotbed in Hong Kong, Libeskind intended to design a building that is more than concrete and glass, allowing creativity to flow freely, like music.

Libeskind says his love of music has infiltrated his approach to design. “Music shapes my idea of a space,” he says. “Space can’t just have the hardware, the infrastructure, the concrete and the glass. It has to have atmosphere, it has to have spirit. There’s not just an intellectual connection, it’s an emotional connection. You can call it intimacy… it’s whether you feel good in a building.”

Find out what A. Eugene Kohn of Kohn Pedersen Fox qualifies as good architectural design.

The difficult topography in Hong Kong played a big part in Libeskind’s design, and it has shaped the Run Run Shaw Media Centre quite uniquely. “It’s very sensitively positioned between the mountains and the water… it comes out of the ground, that crystalline cliff it is part of,” he says. The centre seems to mirror that “crystalline cliff”: skewed geometric shapes emerge like stalagmites from the earth.

Libeskind is best known for creating such asymmetric, rough-cut diamond outlines. In Kowloon Tong, they can be found in the intersecting lines of structural beams, windows, doors and the linear lighting patterns of ceilings. The same shapes are reflected in the rooms, which slope and slice into spaces that function as sound stages, laboratories and more.

“It’s not just a box,” says Libeskind earnestly. “It’s really a response to very interesting creative media. In terms of the functionality, the aim was to create a space for students to interact in inventive ways.”

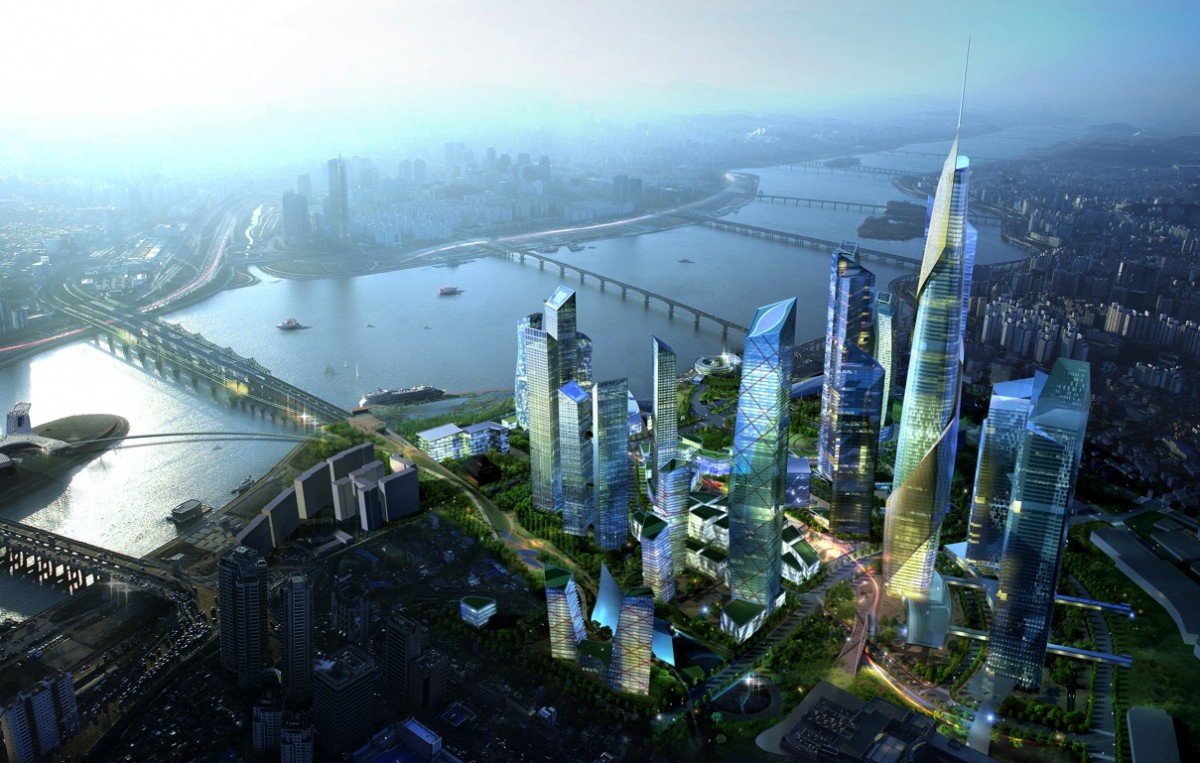

Libeskind is currently in the midst of several projects in Asia, including his residential Reflections at Keppel Bay, Singapore that consists of six high-rise towers and 11 low-rise villa-apartment blocks; the Haeundae Udong Hyundai I’Park in Busan, South Korea, a development that encompasses residential towers, a 34-floor hotel and a retail complex; and Archipelago 21, a vast urban redevelopment in Seoul that will house residential neighbourhoods, shopping areas, cultural sites and a new international business district.

Libeskind is not your typical architect, nor is his creative process common. “I’ve always thought of architecture as much more of an ancient art… [a building] is not a machine to live in, it’s not a mechanical product. [I develop my buildings] from a sketch, from an idea, from a connection with the land and the sky and the people, from a set of small physical models that are very humble. I make a model just like it is a sculpture, to get into the building in an imaginative way,” he explains.

“No matter how avant-garde a building is, if it doesn’t have a secret connection to something ancient, then it’s just an exercise in style,” he offers. “And I’ve never thought that was good enough for architecture.”