Data suggests that having fewer women in science is not only bad for equality, but innovation. We meet Juliana Chan, the publisher and scientist on a mission to smash the glass ceiling

Can you name an Asian female scientist? In fact, can you name any female scientist who isn't Marie Curie? Unless you're in the field yourself, the answer is most likely no. Juliana Chan is on a mission to fix that and help women get on a path to equality in the still male-dominated world of scientific research.

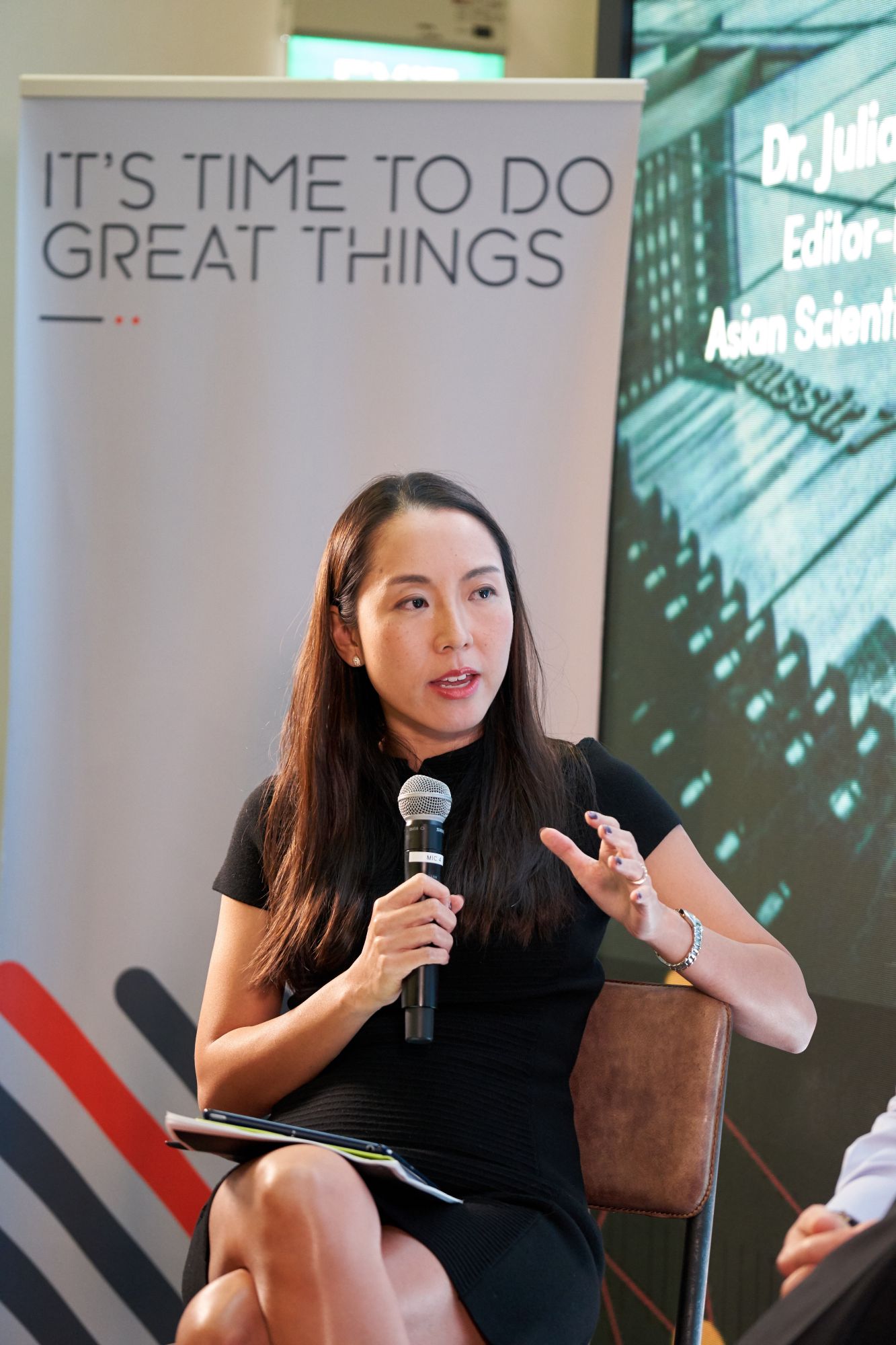

A former research scientist, Chan is currently the CEO of Wildtype Media Group, Asia's leading STEM-focused media company, and the editor of Asian Scientist, the region's largest science magazine. But as well as spreading the scientific word to the masses, she has a very ambitious plan to help women in STEM—in fact that was one of the reasons she left academia.

“There is still so much we can do,” she says, on the phone from Singapore. “One is to reduce the number of men-filled panels, or ‘menels’ as I like to call them. I recently attended a talk with seven men on the panel—could they not have even made an effort to have included one woman?”

In early September, she moderated the 16th Gender Summit, which fights back against the often-held assumption that science is gender-neutral. In fact, research outcomes are frequently worse for women than for men; and men continue to secure the majority of top-level jobs in science, and the majority of research funding.

Studies show that inequality starts right at the beginning of the scientific process—right when researchers petition for money from funding bodies. It had already been shown that men, for instance, have a much higher chance than women of obtaining funding for their research

“We were all very focused on how we could help women in research and development,” says Chan, on the summit. “We were a large group of women from specific industries who came together, and there were speakers from all over the world.”