North Korea hopes to attract two million tourists by 2020, but would you go? We weigh up the risks and rewards of visiting the notorious “hermit kingdom”.

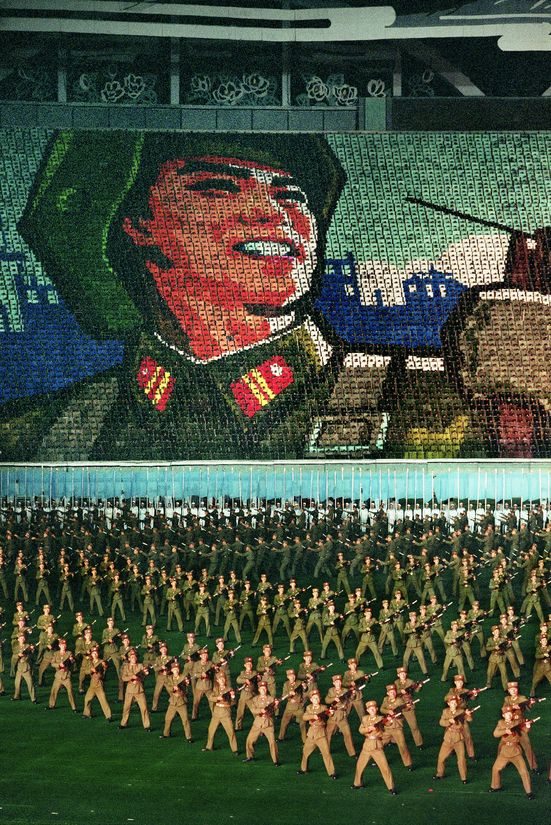

Forget five-star hotels and Michelin-starred restaurants; throw in a controversial dictator, a fraught history and a rule book bigger than the Bible and you have an unlikely tourist hotspot—the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, commonly referred to as the DPRK. While a holiday in a country so politically and socially isolated that it’s known as the “hermit kingdom” might sound absurd, more than 100,000 intrepid travellers venture here annually to get a glimpse of “real life” in this relic of the Soviet era.

The annual Pyongyang Marathon attracted more than 1,000 foreign amateurs last year, up from just 200 when it opened to outsiders in 2014. And, contrary to popular belief, North Korea wants foreign tourists; it aims to be luring two million a year by 2020. But would you go?

A trip to Pyongyang would bestow extraordinary bragging rights, enviable selfies and dinner party conversation for years, but there are very real risks associated with visiting North Korea. Relations between the DPRK and the West are at their shakiest in decades following the testing of Pyongyang’s first intercontinental ballistic missile last year.

As North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un, and US President Donald Trump rattle their sabres, one hopes this talk of war is nothing more than bombastic rhetoric; Washington and Pyongyang have always exchanged insults (although none so colourful as “Rocket Man” and “Dotard”). Further, the grisly fate of 22-year-old US student Otto Warmbier, who was detained in 2016 after attempting to steal a propaganda poster in Pyongyang and returned to his parents blind, deaf and incoherent last year shortly before dying, struck closer to home, stirring a more visceral fear of the regime.

But it’s not just one’s personal safety that should be of concern. Given the DPRK’s abysmal human rights record and its nuclear weapons programme, is travel to North Korea even morally acceptable? Tourism gives the regime a chance to “expose their narrative to people from outside,” says Hamish Macdonald, COO at Korea Risk Group, a specialist information and analysis firm focused on the DPRK, and formerly a reporter at the Korea Herald. Tourism is also a means by which the regime can earn foreign currency. So is this intrepid travel or irresponsible travel?

There's more than meets the eye

Simon Cockerell, general manager of Koryo Tours, has made 164 trips to the DPRK and describes it as “endlessly fascinating.” He is one of many who have visited in recent years who say North Korea’s reality bears little resemblance to the nefarious dystopia painted in the press. “I think anyone who follows North Korea knows that it’s a complicated, frustrating and enigmatic place."

He adds, "that puts some people off because some people don’t want things to be complicated, but it also attracts people because they think there must be more to it than is reported. Even though the side that is not reported is the more banal side, it’s interesting to see this juxtaposition in the era of extreme news."