Instituto Cervantes de Manila recently organised a round table discussion to reflect on the value of San Nicolas, the neighbouring district of Binondo and Intramuros. The main question: is there still hope in saving its historical and heritage value?

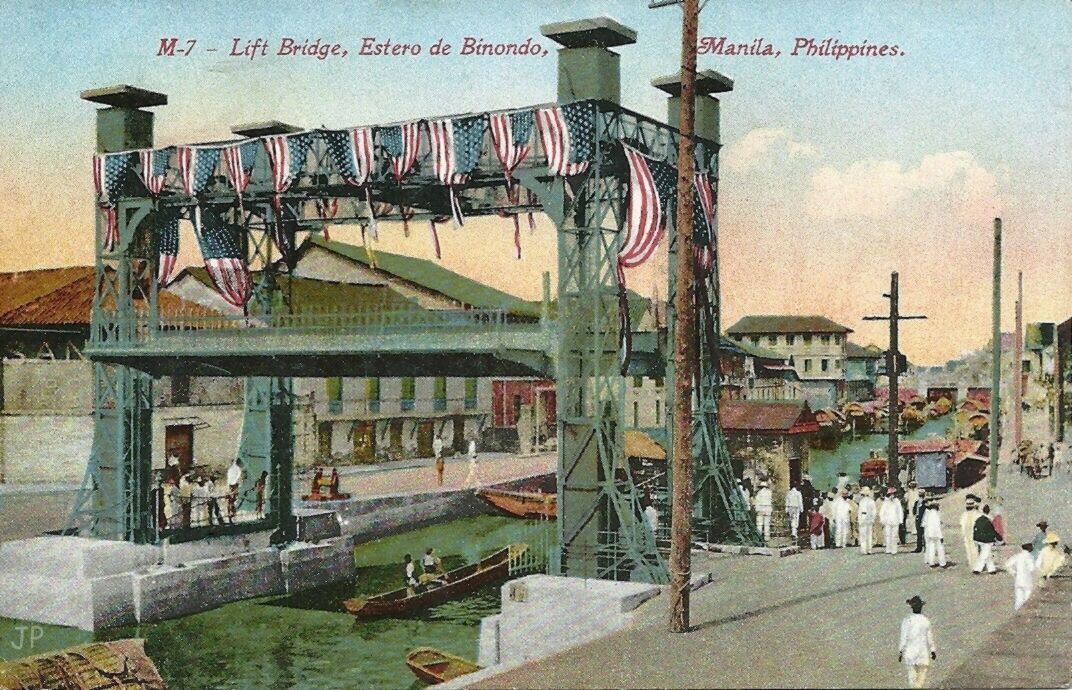

In strolling the busy street of Escolta more than a century ago, one will not yet see the art deco theatres and commercial skyscrapers that would tower it at the dawn of the 20th century. Instead, one would stumble upon Puente de España and Binondo's major thoroughfare Calle Rosario abound with traders, tourists, diplomats, indios and principalias, and devotees of the Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary walking to and fro. Further west, passing through Estero de Binondo lies the district of San Nicolas.

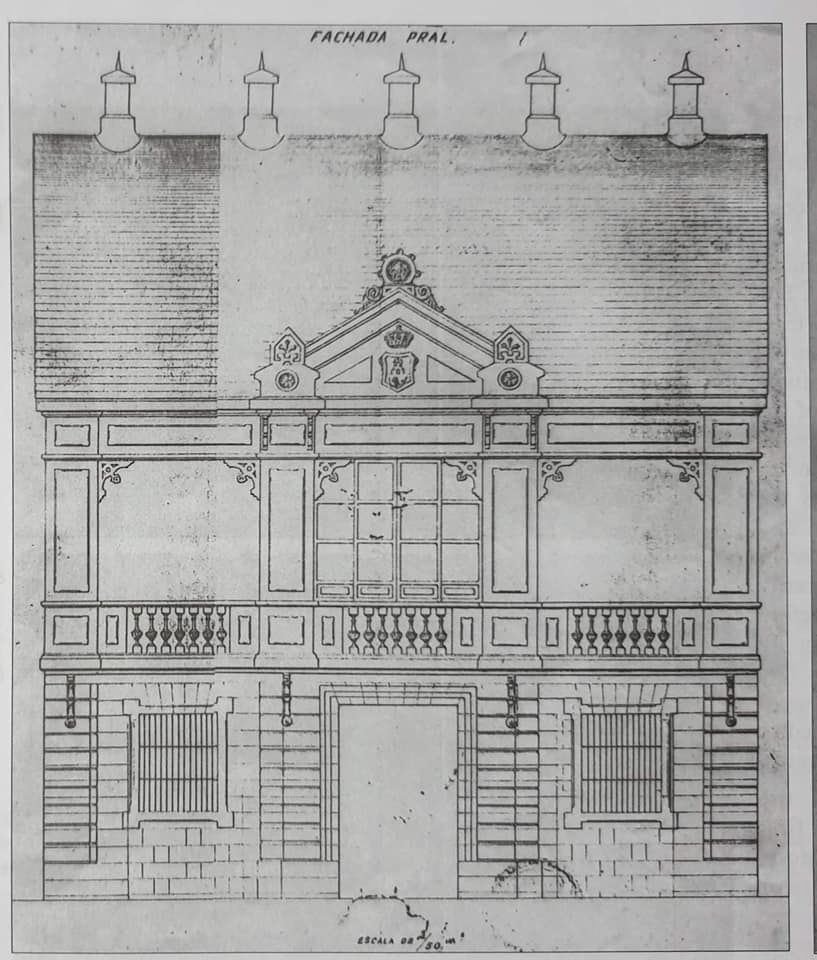

Named after San Nicolas de Tolentino—patron saint of sailors, boatmen, and mariners because the town used to be called Baybay (shore)—the district teems with Filipino craftsmen and artisans making Manila known in the world since the 19th century. Aside from the piers of Manila Bay, at the heart of the district is the foundry of renowned bell caster and metalsmith Hilario Sunico and his family, while the streets of Jaboneros and Ilang-Ilang are known for their soap and perfume-making warehouses with products being shipped to France. Another worth mentioning is the frequented marketplace for quality silk, Alcaiceria de San Fernando, the first and largest commercial structure in the country circa 1756, designed in octagonal format by Fray Lucas de Jesus Maria and built by the Christian Chinese master builder Antonio Mago with piedra china (granite rocks).

Read more: Letras y Figuras: The 19th-Century Philippine Art Form's Origins and Legacy

The Alcaiceria was burnt to the ground in 1850. Soon the great fire of Binondo in 1870 damaged many other structures as well. Though the historic fire paved way for the building of more opulent houses, earthquakes throughout the years shook their very foundations. Fortunately, the Liberation of Manila in 1945 spared the district and left most of the ancestral houses and commercial buildings intact.

But the real enemy of the district was time.

Soon, the structures were left in a decrepit state. Modern, high-rise buildings were built everywhere in replacement for some abandoned heritage houses. A part of the district was later known to be the port of Delpan, which intensely polluted the Pasig River. While Divisoria became the go-to place of shoppers and retailers for cheap knockoffs and wholesale stocks. Casa Vyzantina, a three-storey structure intact with opulent and ornate neo-Mudejar architectural details of the 19th century has been demolished and rebuilt at the Las Casas heritage resort in Bataan.

Read also: A Walk to Remember: Philippines' Heritage Places for Wanderlusts