The Malaysian director Chong Keat Aun, who was named the best new director at the 57th Golden Horse Awards in Taipei, was a youth who lived a simpler life, surrounded by the lush paddy fields of Kedah and the local stories that would soon shape his entire career as a filmmaker

Clutching his award for best new director after the reveal of his first-ever feature film, The Story of Southern Islet, with both hands, Chong Keat Aun’s voice was tremulous as he began his acceptance speech on the night of the 57th Golden Horse Awards, which took place just last year on November 21, 2020 in Taipei, Taiwan. “Movies themselves aren’t extraordinary. In fact, what’s most extraordinary are the people who made them happen,” he says.

See also: Malaysian Filmmaker Quek Shio Chuan Tells Deeply Personal Stories

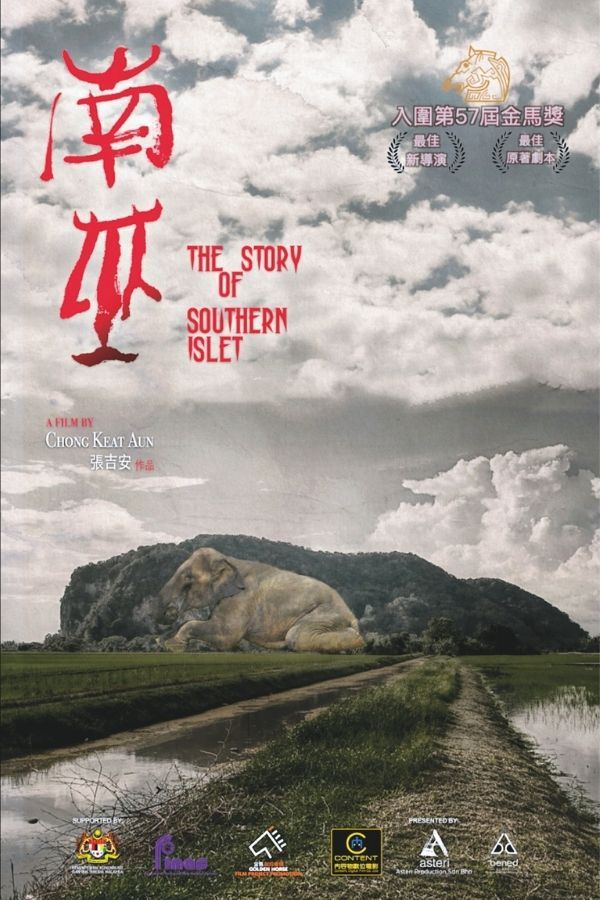

THE STORY OF SOUTHERN ISLET

Set amidst the backdrop of an idyllic countryside in Alor Setar, Kedah during the '80s, Chong’s debut film tells the story of Yan, a woman desperately seeking a cure for her husband Cheong, who, after quarrelling with a neighbour, suddenly falls ill and spits a bloodied, rusty nail. According to the director, the premise of the film had been based on his own childhood events at the age of 10; particularly, the vivid memory of when his own father had succumbed to an unknown, incurable disease that left him weak and bedridden for almost a year.

“Nothing we did could explain what he was sick with, or how he’d gotten it in the first place,” the now 42-year-old explains. “At the time, clinics weren’t readily accessible, and I remember my mother just trying her best to help him get better because my father was so sick that he couldn’t even get up—every day, she’d wake up at 6am, paddle the bicycle to the morning market to sell anchovies, rush back home in the afternoon to cook lunch, take care of my father, then she’d be out the door again to look for help. She never stopped to rest. In the end, when there was no other way, she went in search for Chinese or Malay bomohs.”

In awe of his mother’s determination and inspired by the local folklore he’d grown up with at the time, Chong had wanted to convey a quintessentially Malaysian tale while sharing the journey of a woman so dedicated to her family. Jojo Goh, who plays Yan in the film, echoed the very same sentiment when she first read the script.

“It was rather stressful because the role was written with the director’s mother as a blueprint and the story based on his real-life experiences. I wanted to do those memories justice by bringing them to life, so I needed to understand what was going through her head at the time, the extent of her love for her family as she willingly changes her perception and becomes open to believing in the spiritual.”

See also: 18 Film Directors That You Should Know If You're A Fan Of Asian Cinema