She fell in love with the art form at the age of five. Now she wants to foster the same passion in a new generation of Hongkongers. Daisy Ho tells us about the beauty – and the business – of ballet

The first thing that strikes me about Daisy Ho is how much she looks like a ballerina. Her waist is the width of two pint glasses—an inappropriate analogy, perhaps, as I can’t imagine Ho drinking anything other than champagne—and she moves her delicate body with an elegance that’s usually the preserve of dancers.

“Everybody always asks me if I used to be a professional dancer,” says the daughter of casino mogul Stanley Ho in her soft, measured tones. “But I gave up ballet when I was just six years old because, like so many Hong Kong children, I needed to focus on my schoolwork.” Despite the improbably short period she spent perfecting her demi-pliés and arabesques, a love for the art form remained within her and ended up shaping her future.

“I only practised ballet for a few years, but those lessons became some of the most exciting moments of my life,” says Ho with a bittersweet smile as we chat in her corporate office in the Shun Tak Centre. “I would spend hours at home practising my steps in front of the mirror and I’d then beg my parents to take me to any performance that came to Hong Kong.

“Looking back, I can see that even from a very young age, my feelings for ballet were unusually pure,” she continues. “It wasn’t about the costumes or the set or the fantasy of being a beautiful ballerina; it was about something deeper than that. I genuinely appreciated the posture and poise of these dancers. Watching ballet has always given me a sense of calm while making me feel quite joyful. It is inspirational

in that way.”

In a world that contrasts somewhat with these poetic musings, Ho is the deputy managing director of Shun Tak Holdings. Responsible for the company’s overall financial activities and major property developments, she has one of the most celebrated business minds in the city. It was therefore an inspired move when John Ying, a close friend, nominated her for election as chairwoman of the Hong Kong Ballet, a position that is elected annually. The committee voted unanimously in April last year for Ho to succeed Ying, who was retiring after holding the position for the maximum six years.

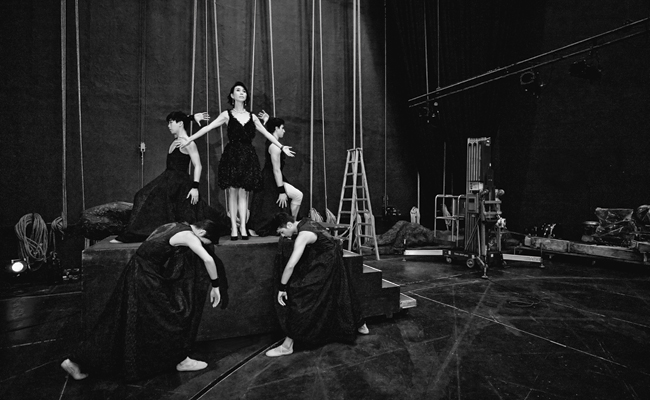

With the ballet celebrating its 35th anniversary this year, many have been reminiscing about its achievements, but Ho has her eyes on the future, keen to ensure the inspirational institution is still delighting audiences for 35 years to come. To this end, she is working on strategies to foster a love of dance in the city’s youth. “I come from a commercial world and, I’m sorry if this sounds too straightforward, but, to me, the ballet is also a product,” she says. “And it’s a product I need to make more popular than it is right now. It’s time to initiate a rebranding exercise—and I’m not just talking about aesthetic rebranding, but about a re-evaluation of our entire situation.”

The crux of the matter is that Ho fears ballet is in danger of becoming a dying art. She no longer senses the same enthusiasm for it in the younger generation and believes that without an urgent rebranding exercise, it could soon become an obsolete dance form—a quaint memory from the past rather than a vivid reflection of modern life.

“Let’s face it, ballet doesn’t have a ‘cool’ factor and it probably never will,” she says pragmatically. “But if I can persuade young people to go to a performance and appreciate the visual beauty, or the music, or the set design, then my job will be done. I think it is entirely possible—and I can give you an example from my own family to explain why. My younger daughter is 17 and not nearly as interested in the art of ballet as I am, but she loves the costumes and theatrics of a big performance, so she always comes with me. I hope that I can foster that mentality in other kids.”

Shaping young people’s tastes is never the easiest of tasks, so how will Ho succeed where so many others have failed? “Through emotion,” she says after a long pause. “Selling properties is simple. There’s no feeling involved and I like it because it’s bricks and mortar and I can be as ruthless as I want. But ballet is different. You need a softer touch because there’s a lot of emotion attached to it. But instead of being afraid of that, I want to harness it and use it to my advantage. I want to inspire people to fall in love with it the way I did.”

Ho believes the focus of her degree from the University of Southern California, marketing, is the key to the project. “I believe that if you want to attract the young people to the art form of ballet, you simply have to learn to speak their language,” she says. “From marketing to the format of our education programme to our programming, there needs to be a creatively formulated and studiously executed development plan that targets our future audience before and during their formative years.”

This relates to another key problem the ballet faces: that people expect to see tutus and tiaras and Swan Lake, and due to this preconception, they reject the rawer, more modern forms of ballet. “The famous classical productions are still better received,” she says. “But every ballet needs its own performances. We have to keep the dancers challenged and we have to create a modern art form that can be appreciated by all generations.”

Paul Tam, the recently appointed CEO of the ballet, agrees with her. “Anywhere in the world, be it New York or Tokyo, dance is always a harder sell than music and theatre,” he says. “I am hoping that in the next decade we will be able to take the ballet to another level artistically, develop a stronger brand and attract more audiences. Having worked with Daisy since January, I can see that she is just the person to take us there due to her exceptional business skills and her passion and love for the organisation.”

Ho’s commitment to the dancers is particularly stirring. “I don’t think many people have a concept of how hard ballerinas work,” she says. “Physically, you have to be really fit to get a simple step right; it takes years of practice. But what I find sad is that once you get to your mid-30s, your career is over. The monetary rewards are never particularly great and I often marvel at the drive and determination of these young people.”

To aid financially, Ho has recently introduced a sponsorship fund through which philanthropists can choose a specific dancer to support and then donate money for essentials such as shoes and physiotherapy. However, she is also looking to help the dancers in a broader sense. “Money is important, yes, but their passion is not monetary; it is about the recognition and gratitude, about the applause and the high they get from that. We need to create a strong audience base for them so they feel received by their own people.”

In a bid to raise money for all these causes, Ho overcame her natural shyness last year and performed in an extract from Swan Lake at the annual Hong Kong Ballet Ball to riotous applause. “I didn’t mind looking ridiculous, as we got some good donations out of it,” she says, with a broad grin spreading across her face for the first time. “And it was Swan Lake, which is my one true love. I was so scared, but once I was out there, dancing,

it felt wonderful.”

It seems that the little ballerina inside Daisy Ho is finally getting out.

This story originally appeared in the December 2014 issue of Hong Kong Tatler