Artist Jenny Saville opens the doors to her studio, where she has painted a new series for an exhibition this month at Gagosian in New York

Two years ago, a painting by Jenny Saville set a record at auction for the highest price paid for a work by a living female artist, but the British painter doesn’t like to think about that too much. “I try to keep my eye firmly on the art; the painting is the same painting as it was before the auction,” she says matter-of-factly, when we meet in her drawing studio in Oxford.

The painting in question is the gargantuan, corpulent self-portrait, Propped, created in 1992 and one of five works by Saville to have been exhibited in the Sensation show of Young British Artists (YBAs) that caused such a stir at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1997. The 2.1-metre-tall canvas sold for Åí9.5 million.

“That’s crazy money, but at the same time, compared to Jeff Koons’ bunny, it’s not crazy,” Saville says, referring to the US artist’s stainless-steel leporine sculpture, Rabbit, which fetched an eye-watering US$91.1 million at auction in 2019, making Koons the most expensive living male artist. By any standard it represents a painfully pronounced gap between the value of art made by men and women, but, as Saville notes, “The good thing is the bar has been set that bit higher for other women artists coming through.”

Beyond Gender

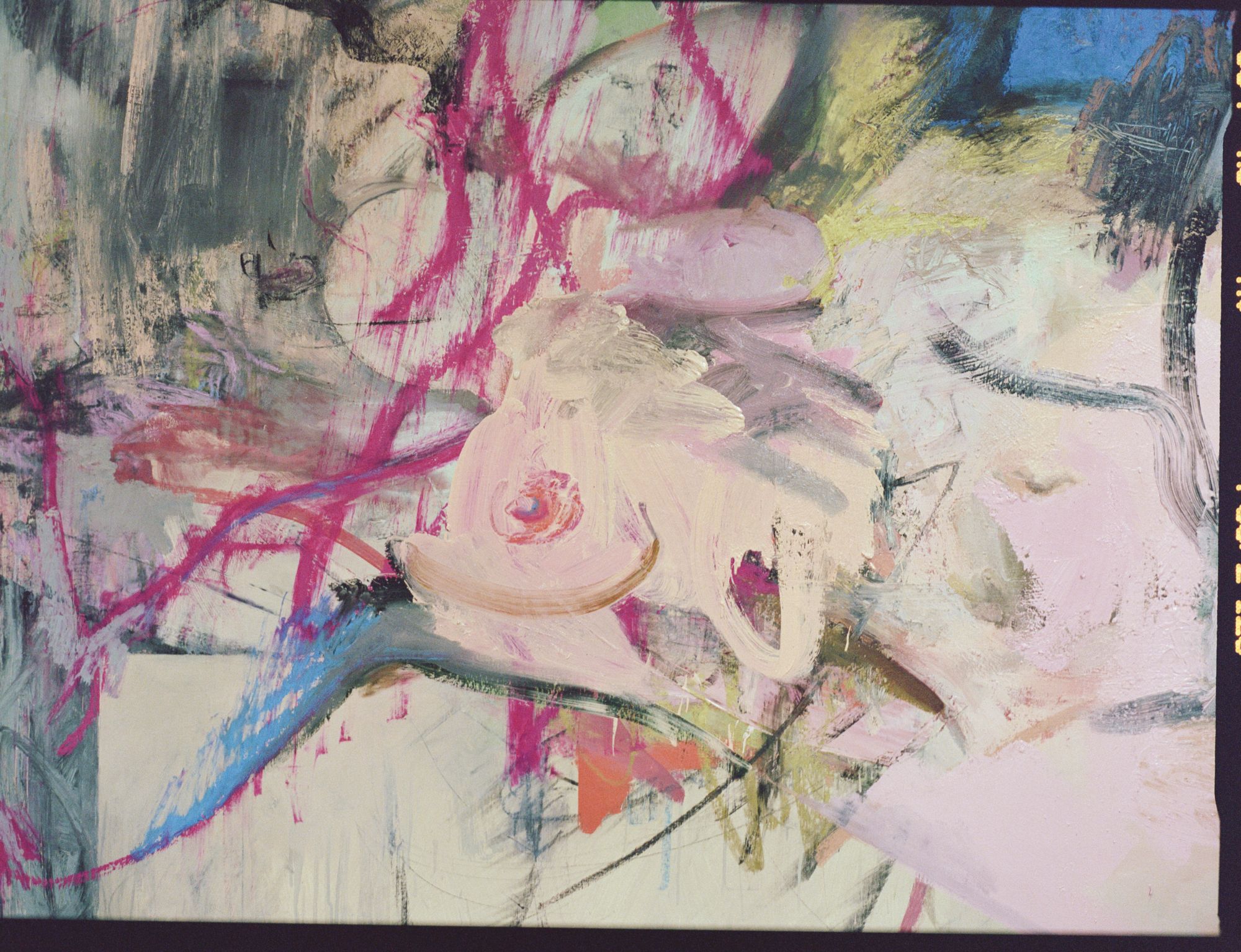

Setting the bar high has been a constant for Saville, who has made a 30-year career out of her love for “the sensuality of flesh”. She started out painting women’s bodies, chiefly her own, but has also turned her gaze on men (Pablo Picasso’s late biographer John Richardson often sat for her). More recently, in works such as Vis and Ramin II (2018) or Out of one, two (symposium) (2016), fluid tangles of male and female body parts merge to create non-binary figures.

“I like the idea of a transgender painting where the work itself doesn’t have a fixed gender,” she says.