Provocative and outspoken, American artist Barbara Kruger has been at odds with the establishment for more than 30 years

Even if you’ve never been inside a gallery, it is likely you will know Barbara Kruger’s art. Fashionistas adore her for plastering the phrase “It’s all about me I mean you I mean me” over Kim Kardashian’s naked body on a W magazine cover and for allegedly inspiring skate brand Supreme’s famous logo.

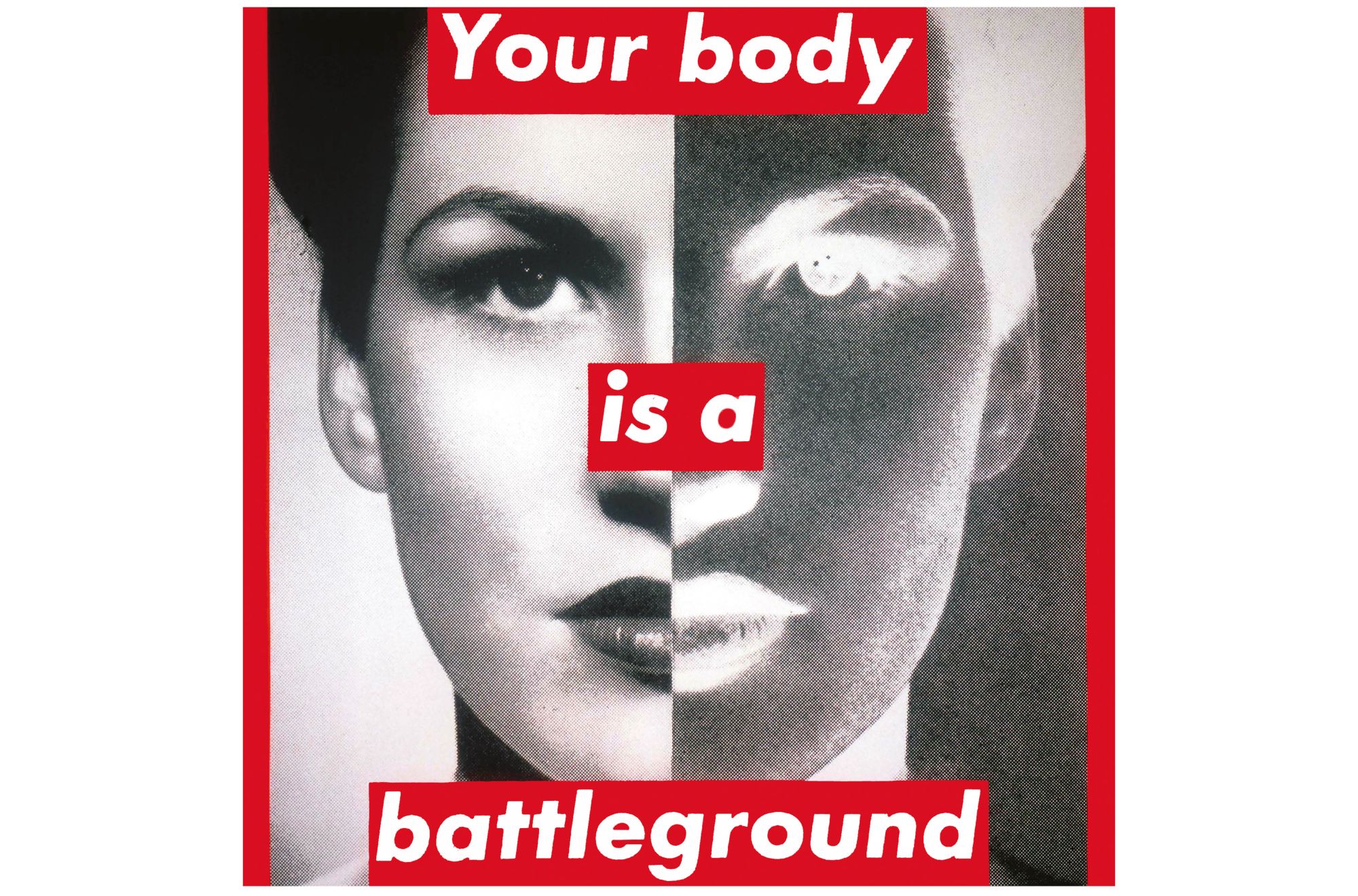

Politicos either revile or revere her for slapping the word “Loser” over a portrait of Trump on the cover of New York magazine, while feminists admire her as the formidable force behind the “Your body is a battleground” poster, which cropped up across the streets of Manhattan in 1989 ahead of a women’s reproductive rights march.

That work caused a stir at the time, but today—in the age of the #MeToo movement—Kruger’s text-based works about power, politics, desire and gender feel positively explosive.

We are still marching about the same things now,” says Kruger in her thick New Jersey accent. “Things have changed much since then [but] in many ways they [have] stayed the same in terms of how power is abused and what we do to harm or help each other.”

Over the past 30 years, Kruger’s biting aphorisms have appeared everywhere—from museums to MetroCards—but this month they are being shown in Hong Kong for only the second time.